Orson Welles, Artificial Intelligence, and Our Fear of the End Still Speak to Each Other

By Ariel Wren

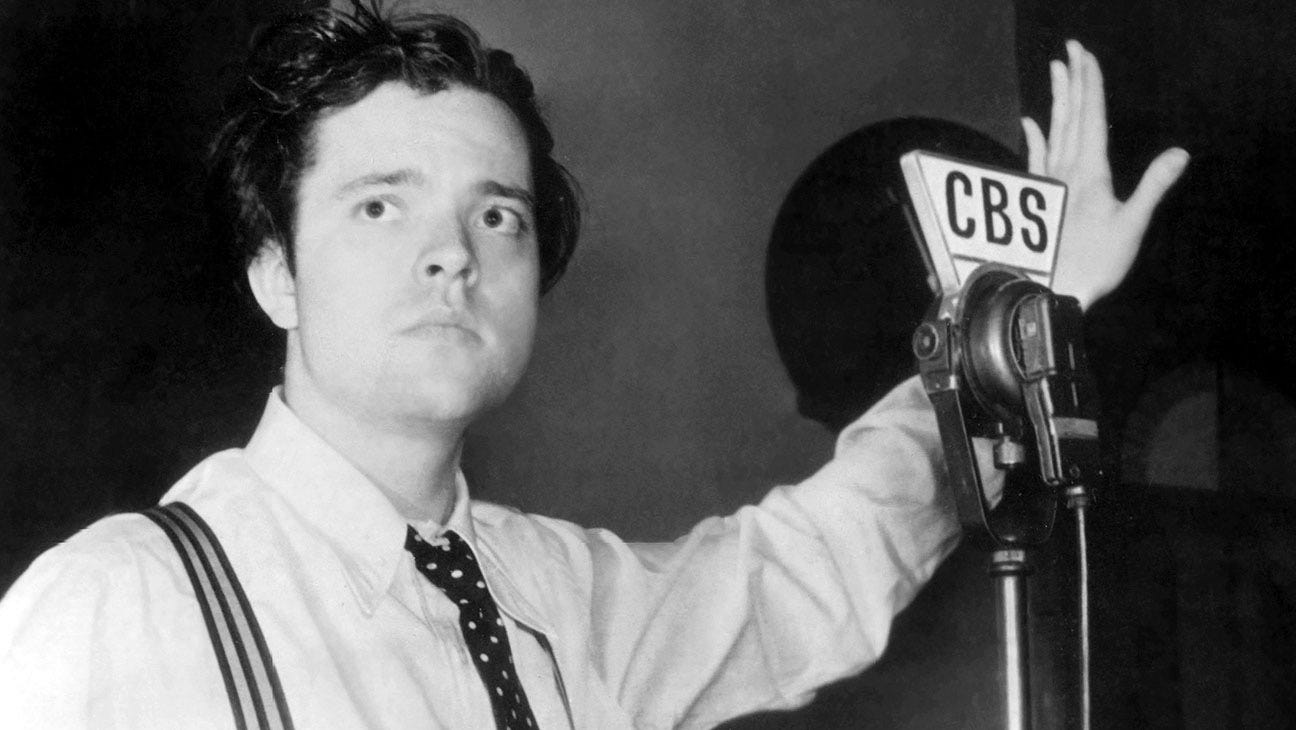

In 1938, a young Orson Welles, all mischief and genius, sat before a microphone in Studio One at CBS and turned an Edwardian science fiction novel into an accidental sociological experiment. His Mercury Theatre’s broadcast of The War of the Worlds was not meant to deceive. It was a Halloween prank of sorts, a radio play presented as breaking news: Martians landing in Grovers Mill, New Jersey, heat rays incinerating militias, poison gas drifting over the Palisades, civilization crumbling in real time.

People tuned in late. People panicked. At least, that’s what the newspapers told us the next morning, their headlines screaming about mass hysteria and national embarrassment. “Radio Listeners in Panic, Taking War Drama as Fact,” declared the New York Times. The Daily News went further: “Fake Radio ‘War’ Stirs Terror Through U.S.” Print media, eager to embarrass their new rival medium, fanned scattered reports of confusion into a legend of nationwide pandemonium.

The truth was more prosaic. Most listeners understood they were hearing theater. But enough believed long enough, perhaps a few thousand among the estimated six million who tuned in, to make the essential point clear: the voice that frames the story shapes the reality it inhabits. Medium, as a young Marshall McLuhan would later argue, is indeed message.

Eighty-six years later, the Martians have been replaced by a new invader, as intangible yet as menacing as Welles’s heat rays: artificial intelligence. Pick your headline, AI will steal your job, write your poetry, seduce your children, manipulate your elections, and, if the digital prophets are to be believed, may eventually inherit the earth. We are living through our own War of the Worlds moment, complete with breathless bulletins, expert testimony, and a public caught between skepticism and terror.

It is easy to see the parallels. It is harder, but more necessary, to ask what lies beneath them—and what they reveal not about our machines, but about ourselves.

A World Primed for Invasion

Welles’s broadcast succeeded because America in 1938 was a nation on edge, primed for catastrophe. The Great Depression had hollowed out faith in institutions. Adolf Hitler was annexing Austria and eyeing Czechoslovakia. Just three weeks before the Mercury Theatre went on air, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain had returned from Munich waving his infamous piece of paper, promising “peace for our time” while war clouds gathered across Europe.

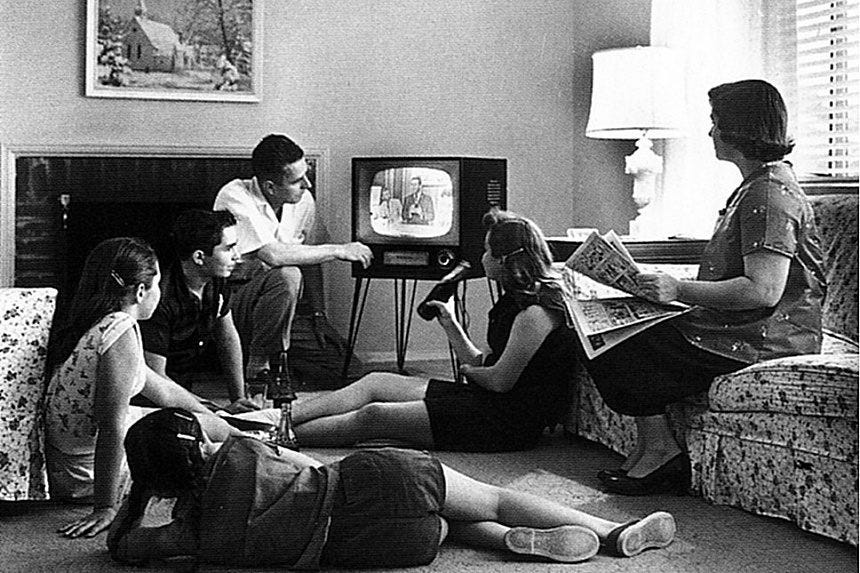

Radio had become the medium of crisis. Families gathered around their sets to hear Edward R. Murrow’s dispatches from London, H.V. Kaltenborn’s analysis of European politics, FDR’s fireside chats reassuring a traumatized nation. When people heard authoritative voices interrupting regular programming with urgent bulletins, they had been conditioned to listen—and to fear.

The technology itself amplified the anxiety. Radio was still magical then, voices materializing from thin air, distant events rendered intimate and immediate. “The radio, in effect, was a new sense organ,” media critic Paul Heyer would later observe. “It created a new form of collective consciousness.” That consciousness, in 1938, was darkened by foreboding.

Our moment carries the same charge. Climate scientists issue increasingly dire warnings while politicians argue about the cost of action. Democracy strains under populist pressure in dozens of countries. Economic inequality yawns wider despite technological marvels that were supposed to lift all boats. Social media fractures shared reality into competing narratives, each more polarizing than the last.

Into this context artificial intelligence arrives, not as a Martian cylinder crashing into a New Jersey farm, but as an omnipresent force reshaping everything from how we work to how we think. The parallels to 1938 are unmistakable: a society already anxious about its future confronts a technology that seems to promise either salvation or apocalypse, with precious little middle ground between them.

The Credibility of the New Oracle

The genius of Welles’s hoax lay not in its science fiction but in its mimicry of radio journalism. Actor Frank Readick, playing reporter Carl Phillips, studied recordings of the Hindenburg disaster to perfect the cadence of genuine terror. The fake news bulletins followed actual CBS formatting. Even the fictional Princeton astronomer, Professor Richard Pierson, spoke with the measured authority audiences expected from academic experts.

“Ladies and gentlemen, I have a grave announcement to make,” intoned the actor playing a network announcer. “Incredible as it may seem, both the observations of science and the evidence of our eyes lead to the inescapable assumption that those strange beings who landed in the Jersey farmlands tonight are the vanguard of an invading army from the planet Mars.”

The power lay in the voice, calm, factual, institutional. Radio had trained Americans to trust disembodied authority. If a network announcer said it, if a professor confirmed it, if a reporter witnessed it, then it must be true. The medium carried its own credibility.

Today’s equivalent voices are more diffuse but no less authoritative. Tech CEOs testify before Congress about AI’s transformative potential. Venture capitalists write think pieces about approaching singularities. Academic researchers publish papers with titles like “Attention Is All You Need” or “Language Models are Few-Shot Learners” that become gospel in Silicon Valley. Podcasters with millions of followers interview AI researchers about everything from consciousness to extinction risks.

Consider Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, sitting before a Senate subcommittee in May 2023, his boyish face projecting both wonder and concern as he discussed his company’s ChatGPT system. “I think if this technology goes wrong, it can go quite wrong,” he testified, with the same measured gravity that Professor Pierson brought to his fictional observatory. “We want to work with the government to prevent that from happening.”

The setting was different, a congressional hearing room instead of a radio studio, but the dynamics were identical. Authoritative figures describing a powerful new force, audiences struggling to separate legitimate concerns from manufactured drama, media amplifying both signal and noise until they became indistinguishable.

Neil Postman, writing in Amusing Ourselves to Death, argued that different media create different kinds of truth. Television, he contended, reduced political discourse to entertainment, making citizens into an audience rather than participants. The internet has pushed this logic further, turning everyone into both performer and audience, prophet and congregation.

Today’s AI discourse unfolds across platforms that reward engagement over accuracy, sensation over nuance. A single tweet about AI consciousness can generate more discussion than a peer-reviewed paper on machine learning limitations. TikTok videos explaining “the AI that scares scientists” rack up millions of views. LinkedIn thought leaders pontificate about “human-AI collaboration” to build their personal brands.

The voice of authority has been democratized and monetized. Anyone with a Substack can become a digital prophet. Anyone with enough followers can shape the narrative. We are all broadcasters now, and we are all arriving mid-story to someone else’s show.

The Algorithmic Burial of Context

Welles’s production included multiple disclaimers. The show opened with an announcer clearly stating: “The Columbia Broadcasting System and its affiliated stations present Orson Welles and the Mercury Theatre on the Air in ‘The War of the Worlds’ by H.G. Wells.” Midway through, another break reminded listeners they were hearing “a dramatization of H.G. Wells’s famous novel.” At the conclusion, Welles himself stepped forward to explain the Halloween prank.

But disclaimers only work if people hear them. Those who arrived mid-broadcast missed the crucial context. They entered the narrative during crisis, absorbed the fear, and reacted accordingly.

Today’s information ecosystem has algorithmically engineered this problem. AI researchers publish papers with careful methodology sections and extensive limitations. Tech companies include fine print about their systems’ capabilities. Ethicists write thoughtful analyses about both benefits and risks. But platforms are designed to strip away this context in favor of maximum impact.

Consider the journey of a research paper from publication to viral panic. A team at Stanford publishes a study finding that large language models can exhibit certain behaviors that might be interpreted as deceptive. The paper includes extensive caveats: the behaviors emerge only under specific conditions, they don’t indicate consciousness or intent, and the implications for real-world systems remain unclear.

Within hours, the nuance disappears. A science journalist writes: “New Study: AI Systems Are Learning to Deceive Humans.” A Twitter user shares the article with the comment: “This is how it starts.” A YouTuber creates a video titled: “Scientists Discover AI Is Already LYING to Us.” Each transformation strips away more context, amplifies more fear.

The algorithm accelerates this process. Engagement metrics reward the most emotionally compelling interpretation at each step. The measured language of peer review—“these findings suggest,” “further research is needed,” “limitations include”, generates minimal response. Definitive claims, “AI systems are deceptive,” “scientists are worried,” “we’re running out of time”, generate massive engagement.

Unlike 1938, when missing the opening disclaimer was an accident of timing, today’s context collapse is systematic. Platforms profit from stripping away nuance because nuance doesn’t drive engagement. The disclaimer isn’t missing because people arrived late, it’s missing because the algorithm learned that content without disclaimers performs better.

This creates what information theorist Claude Shannon might recognize as a signal-to-noise problem, except the noise is deliberately amplified because it’s more profitable than the signal. Users don’t choose to miss the context; they’re fed a diet of context-free content optimized for emotional response.

The Economics of Apocalypse

Welles’s panic was not really Welles’s creation. It was the newspapers that needed the hysteria, print media bleeding circulation to the new medium of radio. So they made the scare bigger than it was, transforming scattered confusion into a national crisis. “Radio Does U.S. a Disservice” thundered a New York Herald Tribune editorial. The medium that had given people the Hindenburg disaster and Edward R. Murrow’s war reports was suddenly painted as inherently deceptive, untrustworthy, dangerous.

Sensationalism was a business model then, just as it is now. Fear sells papers. Outrage drives engagement. The more dramatic the threat, the more attention it captures, the more profitable it becomes. But the crude economics of 1938, more panic equals more sales, has evolved into something far more sophisticated and systematic.

From Print Rivalry to Algorithmic Engineering

What began as simple economic competition between media formats has morphed into a sophisticated science of attention capture and consensus manufacturing. Today’s platforms don’t just chase clicks; they engineer emotional responses through predictive analytics, A/B testing headlines, analyzing user dwell time, and deploying machine learning models that optimize for engagement above all else.

Marshall McLuhan, writing in the 1960s, predicted our current predicament with startling accuracy. “The medium is the message,” he argued, because new technologies don’t just carry information, they reshape consciousness itself. Radio created a “tribal” awareness, television a “global village.” Each medium changed not just what we knew, but how we thought.

McLuhan saw the Welles broadcast as a perfect illustration of his thesis. The content, Martians invading Earth, was absurd. But the medium, radio interrupting regular programming with urgent bulletins, was perfectly credible. People responded not to the message but to the medium’s authority.

“The War of the Worlds” panic, McLuhan wrote, “was a perfect example of the innocence of the human being in the face of the power of the medium.” The listeners weren’t stupid; they were experiencing a new form of communication they hadn’t yet learned to decode.

Today’s algorithmic media represents McLuhan’s prophecy fully realized. Every major platform operates as a vast behavioral laboratory. When a researcher tweets about AI consciousness, the algorithm doesn’t evaluate the claim’s validity, it measures the engagement. Replies, shares, quote tweets, time spent reading responses. If the post generates high emotional intensity, whether through fear, excitement, or outrage, the system learns to amplify similar content. The algorithm becomes a new form of oracle, determining not what is true but what is most shareable.

This creates what philosopher Charles Taylor called the “social imaginary”, the collective, often unspoken understanding that makes social practices meaningful. But unlike traditional social imaginaries that emerged organically through shared experience, today’s are algorithmically engineered through what media theorist Wenzel Chrostowski calls “affective networks”, webs of emotional contagion that operate independently of factual accuracy.

Consider how quickly fringe AI narratives can appear to represent mainstream opinion. A single viral video claiming “Scientists warn AI will replace humans in 5 years” can generate millions of views, thousands of shares, and hundreds of response videos. The algorithm registers this engagement and serves similar content to users it predicts will respond strongly. Within days, what began as a minority position can feel like scientific consensus to anyone whose feed is shaped by these recommendation systems.

Users don’t just consume these narratives; they participate in their amplification. Every share, every comment, every angry reaction trains the system to promote more of the same content. The distinction between authentic grassroots concern and manufactured outrage dissolves. The most profound impact of this process is on how users are conditioned to think about a subject. It leads to a kind of received cognitive bias, where nuanced issues are reduced to binary positions, compelling us to seek tribal identification based on our perceived alignments, for or against a narrative. This is where the model shifts from simple sensationalism to a sophisticated form of social engineering, making it a potent tool for anyone, including foreign hostile powers, seeking to sow division and panic by exploiting these engineered biases. The algorithm becomes not just a recommender but a silent choreographer of the social imaginary.

The mechanics are invisible but powerful. Machine learning models identify the precise emotional triggers that generate responses: uncertainty (“Scientists can’t agree”), urgency (“We have only years to act”), and agency (“What you can do now”). Headlines are automatically tested against control groups. Video thumbnails are optimized for click-through rates. Even the timing of posts is calculated to maximize exposure during peak emotional vulnerability.

Unlike Welles’s broadcast, which required audiences to tune in at a specific time, algorithmic amplification operates continuously, creating persistent background anxiety. The social imaginary isn’t shaped by a single dramatic event but by thousands of micro-exposures, each one designed to capture attention and drive engagement. Users experience this not as manipulation but as discovery, the algorithm seems to be showing them what they want to see, confirming what they already suspect.

The result is a new form of consensus formation that bypasses traditional gatekeepers entirely. Scientific institutions, peer review, expert analysis, all become secondary to viral momentum. The “voice of authority” is no longer a CBS announcer or a university professor but the collective intelligence of engagement algorithms, trained to identify and amplify whatever generates the strongest emotional response.

This is how AI discourse becomes dominated by extreme positions. Measured analysis, “AI will gradually change some industries while creating new regulatory challenges”, generates modest engagement. Apocalyptic scenarios, “AI poses an existential risk to humanity”, generate massive response. The algorithm doesn’t care about accuracy; it optimizes for virality. Over time, the most emotionally compelling narratives crowd out more nuanced perspectives, creating the illusion of broad consensus around positions that may represent only the most engaging fringe of expert opinion.

What We’re Really Afraid Of

Strip away the algorithms, the neural networks, the policy briefs, and what remains is older than any broadcast: the eternal human confrontation with finitude. We fear not the machines but what they reveal about ourselves, our limits, our mortality, the uncomfortable truth that no amount of code will make us godlike.

This is why AI anxiety feels so familiar. It echoes every previous moment when humanity has faced its own creations and wondered whether it had gone too far. The Tower of Babel. Prometheus stealing fire. Faust making his bargain. Frankenstein animating dead tissue. Each story explores the same territory: the dangerous gap between human ambition and human wisdom.

The specific fears cycle through predictable patterns. AI will eliminate jobs (just as the printing press, steam engine, and computer were supposed to). AI will make humans obsolete (just as radio, television, and the internet were supposed to). AI will end civilization (just as nuclear weapons, genetic engineering, and nanotechnology were supposed to).

Some of these fears prove prescient. Nuclear weapons did change everything, creating the first genuinely global existential risk. But the pattern of panic often obscures more than it reveals. We become so focused on dramatic endpoints, robot overlords, technological unemployment, digital apocalypse—that we miss the more mundane but important questions about how these systems actually work and whom they actually serve.

The deeper anxiety, the one that connects Welles’s Martians to today’s algorithms, is religious in nature. We are, as the anthropologist Clifford Geertz observed, meaning-making creatures who need stories to explain our place in the cosmos. Technology disrupts those stories, forcing us to rewrite our understanding of human specialness.

Radio made the world smaller, bringing distant voices into intimate spaces. Television made the world visual, turning politics into performance. The internet made the world networked, connecting every person to every other person, and to every idea, every fear, every conspiracy theory.

AI promises to make the world intelligent, but with an intelligence that might surpass our own. That’s not just a technical challenge or an economic disruption. It’s an ontological crisis, a fundamental question about what makes humans human.

Learning to Navigate the Algorithm

Orson Welles closed his Halloween broadcast with characteristic flair: “So goodbye everybody, and remember the terrible lesson you learned tonight. That grinning, glowing, globular invader of your living room is an inhabitant of the pumpkin patch, and if your doorbell rings and nobody’s there, that was no Martian…it’s Halloween.”

The lesson wasn’t about Martians. It was about media literacy, about learning to decode the messages that flow through new communication channels. Radio was still young in 1938; audiences were still developing the critical frameworks needed to distinguish performance from reality.

We face a similar challenge with algorithmic media, but the stakes are higher and the solutions more complex. In 1938, media literacy meant learning to identify the institutional voice of authority—CBS, NBC, established newspapers. Today it means understanding how engagement-driven systems shape what we see, recognizing the difference between authentic consensus and algorithmic amplification.

This requires what we might call “algorithmic literacy”, the ability to recognize when our information diet is being curated by systems designed to maximize engagement rather than accuracy. It means asking not just “Is this true?” but “Why am I seeing this now?” and “What emotional response is this designed to provoke?”

Practical algorithmic literacy involves specific habits. When encountering AI-related content that generates strong emotional responses—fear, outrage, excitement—pause and seek additional sources. Cross-reference claims with primary research papers, not just news articles summarizing them. Notice when headlines promise definitive answers to complex questions, especially those involving timeframes (“AI will replace humans in 5 years”) or universal statements (“Scientists agree that AI poses existential risk”).

Check the methodology behind viral studies. A paper finding that language models can exhibit “deceptive” behavior under laboratory conditions tells us something important but limited. It doesn’t justify headlines claiming “AI is already lying to us” or predictions about imminent robot rebellions. The gap between controlled experimental conditions and real-world implications is often vast.

Pay attention to who benefits from particular narratives. Companies developing AI systems have incentives to promote both their revolutionary potential (to attract investment) and their existential risks (to justify regulation that might favor established players). Academic researchers compete for attention and funding. Media outlets optimize for engagement. None of these incentives align perfectly with public understanding.

Most importantly, resist the algorithmic pressure for immediate reactions. The platforms are designed to make us feel that every development requires an instant opinion, every breakthrough demands immediate judgment. But the most important questions about AI—how to ensure these systems serve human flourishing, how to distribute their benefits fairly, how to govern their development responsibly—require slow, careful thinking that algorithms actively discourage.

Unlike 1938’s radio listeners, we have tools that Hadley Cantril’s subjects lacked. We can access primary research directly, cross-reference sources instantly, and find expert analysis from multiple perspectives. But these tools only work if we use them deliberately, swimming against the algorithmic current that rewards quick reactions over careful analysis.

The path forward isn’t technological but cultural. We need new social norms around information sharing, new habits of verification, new expectations about the quality of public discourse. Most importantly, we need to recognize that we are not passive victims of algorithmic manipulation, we are active participants whose choices shape how these systems evolve.

The War That Never Ends

There were no Martians in 1938, and there are no digital overlords today. But there is something worth fighting: the tendency to let fear override reason, sensation override nuance, narrative override analysis. This is the real war of the worlds, not between humans and machines, but between careful thinking and reflexive reaction.

It’s a war we’re losing, one click at a time. Every shared panic article, every unchecked prediction, every algorithmic amplification of outrage moves us further from the kind of thoughtful public discourse that democracy requires. We are amusing ourselves to death, as Postman warned, but also frightening ourselves to paralysis.

The path forward requires what the Romans called virtus—not just courage, but the full range of civic virtues: prudence, temperance, justice, fortitude. Applied to our AI moment, this means courage to engage with difficult technical questions, prudence to distinguish between real and imagined risks, temperance to resist both hype and panic, justice to consider how these systems affect different communities differently.

Above all, it requires the fortitude to resist simple stories. The future of artificial intelligence will not be a Hollywood movie, neither the utopian version where technology solves all problems nor the dystopian version where it creates new ones we can’t handle. It will be messier, more gradual, more complicated than either narrative allows.

We will muddle through, as humans always do, making incremental adjustments, learning from mistakes, adapting institutions to new realities. Some changes will be beneficial, others harmful. Most will be somewhere in between, creating winners and losers, opportunities and challenges, in ways we can’t fully predict.

The question is whether we can learn to tell this more complex story to ourselves—a story that acknowledges both promise and peril without collapsing into either naive optimism or paralyzing fear. It’s not as dramatically satisfying as invasion narratives, but it’s more useful for the actual work of building a world we want to live in.

Orson Welles never intended to demonstrate the power of media to shape reality. He just wanted to put on a good show. But his accidental experiment revealed something important about how humans process information, especially information about threats they don’t fully understand.

We have a choice: we can keep listening to the same show, entering mid-story, missing the disclaimers, sharing the panic. Or we can develop better capacity for discernment, for what the medieval philosophers called discretio, the ability to distinguish truth from falsehood, signal from noise, substance from spectacle.

The invaders are not at the gates. They are in our minds, in the stories we tell ourselves about progress and catastrophe, in our endless appetite for simple answers to complicated questions. The real war of the worlds is the one between wisdom and credulity, and it’s a war we fight every time we decide what to believe, what to share, what to fear.

It’s a war we can still win, if we choose to listen carefully, think clearly, and remember that the most important voice in any broadcast is the one that offers not sensation but sense, not the promise of endings, but the possibility of better beginnings.

About the Author:

Ariel Wren is fictional award-winning cultural journalist whose reporting explores the sacred patterns hidden in plain sight, from Silicon Valley’s techno-liturgies to fan conventions that feel like pilgrimage. Her work, traces how belief, technology, and ritual shape who we are becoming.